Georg Wilhelm Schimper

In Abyssinia. Observations on Tigre

Biography

Schimper Internet Edition

Biography of Georg Wilhelm Schimper

Schimper’s Life and Work

Introduction

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Georg Wilhelm Schimper [Fig. 1], was a renowned German

botanist and explorer who spent more than 40 years in Ethiopia collecting

plants, mainly in Tigray, the Semen Mountains and the Märäb and Täkkäze regions

of what is now known as the Ethiopian highlands and Eritrea. Schimper is now

universally considered to be the single greatest contributor to the knowledge

of the flora and fauna of the Horn of Africa. The great majority of plants of

Ethiopia had been unknown in Europe before Schimper visited the country. He

went on many expeditions to collect plants which he then dried and sent as

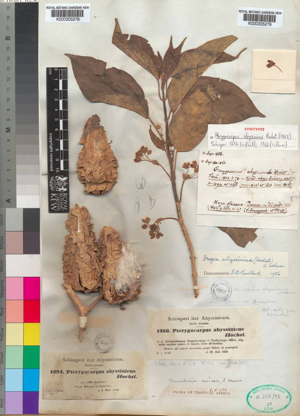

Fig. 2

specimens to European herbaria. They still form a substantial part of the collections

of major research centres in Europe such as the Jardin des Plantes in Paris,

the Botanisches Museum in Berlin, and the Royal Botanical Society at Kew in

London and many others.[1]

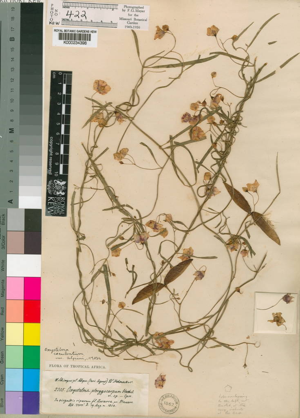

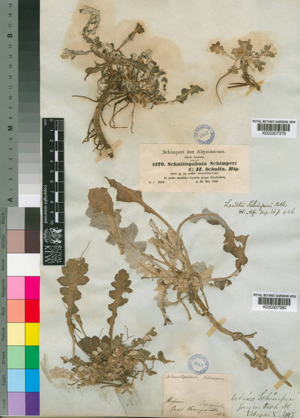

The Kew Herbarium catalogue alone reveals some 2400 schimperi or schimperiana

entries for plants he classified and described in Ethiopia and the

countries he visited in the Middle East [Fig. 2; Fig. 3].

Fig. 2

specimens to European herbaria. They still form a substantial part of the collections

of major research centres in Europe such as the Jardin des Plantes in Paris,

the Botanisches Museum in Berlin, and the Royal Botanical Society at Kew in

London and many others.[1]

The Kew Herbarium catalogue alone reveals some 2400 schimperi or schimperiana

entries for plants he classified and described in Ethiopia and the

countries he visited in the Middle East [Fig. 2; Fig. 3].

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The documents by and about Schimper, which are to be found in various archives in Europe, form extremely important records not only of the botany, but also of the geology, mineralogy, meteorology and topography of Ethiopia. This evaluation and sketch of his life is followed by a discussion of his most important two research papers on the botany and geology of Tigray and Bägemder, Northern Ethiopia, which are kept in the British Library in London.

Schimper’s biography

Schimper was born on 2nd August 1804 in Lauf on the River Pegnitz near Nuremberg in Germany. He was the second son of Friedrich Ludwig Heinrich Schimper, a teacher of engineering and mathematics, and Margaretha Baroness von Furtenbach, a descendant of an impoverished aristocratic family from Reichenschwand in Bavaria, Germany.[2] Georg Wilhelm Schimper came from a family of scientists; his elder brother, Karl Friedrich Schimper (1803-1867), developed glacial theories about the Ice Age and his cousin, Wilhelm Philipp Schimper (1808-1880), a celebrated expert on mosses and bryophytes, became the director of the Strasbourg Natural History Museum.

Schimper’s parents had an unhappy marriage and they separated when he was only 10 years old. His father eventually died in poverty in St Petersburg in 1823 and his mother spent many years in mental institutions where she died in 1833. As a result Schimper and his brother had to rely on the charity of other family members for their education. Schimper attended school at Mannheim and Nuremberg but his formal education ended when he was 14. He then served an apprenticeship as wood turner at Nuremberg before joining the Badisches Infanterie Regiment, working as farrier and gaining the rank of Sergeant. On leaving the army in 1828 Schimper joined his brother Karl Friedrich in Munich, who was enrolled at the University studying Natural Sciences. Although Schimper never actually completed a formal course of study he enjoyed the company of some of the brightest students of his generation. They included Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), paleontologist, geologist and a prominent innovator in the study of the earth's natural history, and Alexander Braun (1805-1877), the German botanist and later Director of the Berlin Botanical Garden. In 1830 he met Eduard Rüppell (1794-1884), the first naturalist to travel in Ethiopia. Ever short of funds Schimper supported himself by working for some of these scientists.

Despite his lack of formal qualifications, he was locally known as ‘hakim’, ‘doctor’ and he himself recounted treating people, for instance healing a relative of Webe’s of an eye infection.[3] In later life Schimper signed his letters as ‘Dr. Schimper’ when writing from Ethiopia, He also signed as Baron von Furtenbach when it suited him.

Collection expeditions

On 25 January 1831 Schimper left Mannheim for his first botanical expedition to the south of France and Algiers in the service of the Botanischer Reiseverein of Esslingen, a travel association (also known as the Unio Itineraria) founded by the botanists Christian Ferdinand Friedrich Hochstetter (17871-1860) and Ernst Gottlieb von Steudel (1783-1856). The travel association was established to promote scientific investigation through the collection and distribution of exsiccatae or dried plants as collectors usually supplied multiple specimens of one plant. The directors raised funds for the scientists from subscribers to the project as well as from the liberal patronage of William I, King of Württemberg (1781-1864) and would then sell on multiple specimens to herbaria all over Europe.

Schimper returned from Algiers due to illness in 1832. For a short time he stayed with Louis Agassiz in Neuchâtel where he continued his work as a draftsman and illustrator, mounting fish skeletons and learning the craft of preserving botanical specimens. Later he stayed with relatives in Alsace. Under the auspices of C. F. F. Hochstetter and E. G. von Steudel, he published an account of his travels, Reise nach Algier in den Jahren 1831 und 1832, in Esslingen in 1834.

In August 1834 he set out on another collection expedition, this time for Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula, for the Travel Association. He travelled with a colleague, Dr. Anton Wiest (1801-1835). They suffered shipwreck near the island Kefalonia, but took the opportunity to explore parts of Greece and the Ionian Islands before travelling on to Egypt. Unfortunately, after having reached Cairo, Wiest died of the plague. Undeterred, Schimper decided to continue collecting plants on the Arabian Peninsula on his own. His first collection comprised some 30,000 plant specimens,[4] which he sent to Germany. In 1835, Schimper was made an Honorary Member of the Mannheim Society for Natural Sciences (Naturforschende Gesellschaft Mannheim) in recognition of the many plants he had sent to his home town.

In the long run, the collection activity proved too costly for the Travel Association. Schimper had sent a request for additional funds, the directors had asked their subscribers to double their contributions, but their support could not be sustained and the Association was wound up in 1842.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

In 1837 Schimper travelled to Massawa on the Red Sea coast and from there overland to the city of Adwa in Tigray, Ethiopia, where he was granted permission to settle under the protection of the local overlord, Ras[5] Webe Haile Maryam (1799-1867). He conducted field trips in the unexplored Semen Mountains, periodically sending botanical collections to Mannheim, for which he was paid in cash. He named a flower after Webe, ‘Ubyaea Schimperi’,[6] the specimen in the Kew Herbarium, dated 30 May 1838, is now called Haplocarpha schimperi [Fig. 4] or Ethiopian daisy [Fig. 5].

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Between October 1837 and May 1855 Schimper undertook various collecting expeditions as far north as the Märäb River and south into the Täkkäze and Semen Mountain regions, the prolific results of which made him the renowned botanist. After the first shipments of specimens from Ethiopia to Mannheim in 1838, 1841 and 1843[7], he continued sending plant collections to other European collectors, to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris from 1851 to 1855 and to Alexander Braun and Georg August Schweinfurth, the celebrated traveller, botanist and ethnologist (1836-1925) in 1854, 1861 and 1862 to Berlin.[8]

Money problems

Through contacts with the Italian Lazarist priest, later Bishop Giustino de Jacobis,[9] Schimper converted to Roman Catholicism on 16 April 1843 and on 22nd April 1843 married an Abyssinian Catholic convert, Wäyzäro[10] Mersit (c. 1823/28-1869). She was a relative of the diplomatic envoy, Catholic convert and priest, Abba[11] Emnätu and believed by many to have been a relative of Webe’s. The couple had three children, Yäsimmäbet Dästa Maria (b. 1843), Taytu Sophie (b. 1845) and Engedasät Wilhelm (b. 1847). A third daughter, Teblat, was born in c. 1853 whilst he was working on the construction of a church for Ras Webe at Däräsge Maryam in the Semen Mountains, although it is not clear whether Wäyzäro Mersit was her mother.

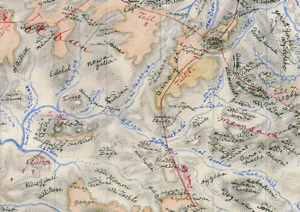

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Also through the good offices of Bishop De Jacobis, in 1843 Ras Webe

appointed Schimper Šum[12]

or governor of the province of Enticho[13]

to the east of Adwa and gave him a small estate there[14] where he introduced

new agricultural methods and plants, among them the cultivation of potatoes.[15] In Amba Sea, he built

a house which he called Gässa Schimper; in later years he entered its location

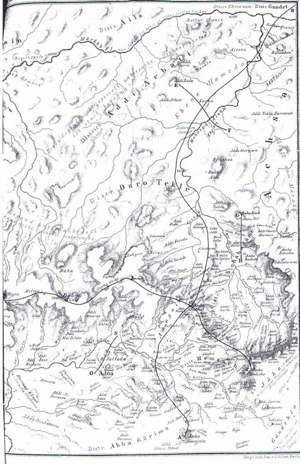

both in his manuscript map [Fig. 6] and in one of the additional tables

Fig. 7

[Fig. 7][16]

and its print version published by A. Sadebeck in 1869 [Fig. 8].[17] One of the houses on

the estate served as R. Catholic church.[18]

Fig. 7

[Fig. 7][16]

and its print version published by A. Sadebeck in 1869 [Fig. 8].[17] One of the houses on

the estate served as R. Catholic church.[18]

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Under Webe’s protection Schimper now had an income from his province of Enticho, but its administration left him very little time for botanical research. All his life he had been hampered by a lack of financial resources and it was a precarious existence to be cut off from European funds. In 1840 and 1843, he tried to interest William I, King of Württemberg, to finance further expeditions,[19] in 1847, he suggested to the Hapsburg Monarchy to start trading with Ethiopia offered his services to enter on behalf of the Austrian consular agencies into commercial negotiations with the Turkish governor of Suakin and Massawa and the Turkish Pasha of Jeddah.[20] Nothing further was heard of these initiatives.

Collaboration with Eduard Zander, a German compatriot

In late 1847 the German artist Eduard Zander (1813-1868) arrived in Adwa and met Schimper. By January 1848 Schimper and Zander left together for botanical collection expeditions in Tigray and the Semen Mountain range. Schimper had been able to appoint a steward to look after his affairs during his absence.[21]

Schimper and Zander, though compatriots, did not always see eye to eye with each other as they supported different political factions, but from 1866 onwards they were both hostages of Emperor Tewodros, and suffered the same fate as all the Europeans in the Emperor’s power. Both stayed in the country until their deaths, Schimper in 1878, Zander in 1868. Until 1855, when Webe lost out to Tewodros, the two Germans shared many tasks at the behest of Webe, who had extended his protection over a number of Europeans on the clear understanding that they had to assist him in any which way he required. This meant that both had to perform tasks for which they had no experience or training.

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

In 1848 Webe commissioned the two Germans to build a church [Fig. 9] and a small stone

building [Fig. 10] at Däräsge Maryam in the Semen Mountains, which they completed in

1853. Schimper

called the

building ‘a small castle’[22] and even used the term ‘Byzantine castle’.[23] Recent research by Manfred Kropp

established that the church was founded with the privileges of an asylum

church, so that the church compound with the stone building was founded as a

place of refuge.[24]

Fig. 10

Imperial foundations were frequently endowed with privileges, laid out in

‘endowment charters’, which specified the privileges like giving shelter,

asylum or refuge to fugitives. In addition, the stone building in particular

had been intended to be the ‘coronation house’.[25]

Fig. 10

Imperial foundations were frequently endowed with privileges, laid out in

‘endowment charters’, which specified the privileges like giving shelter,

asylum or refuge to fugitives. In addition, the stone building in particular

had been intended to be the ‘coronation house’.[25]

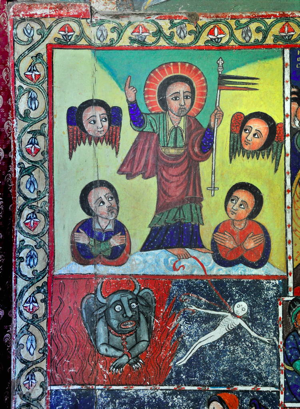

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

The impressive buildings are still standing and well preserved to this

day, the

house of refuge less so. The four walls of the mäqdäs, the sanctuary in the church, are magnificently painted throughout and

Schimper and Zander are said to have superintended the floral decoration depicted

Fig. 12

in the paintings [Fig. 11].[26] Webe endowed the church

with many treasures, amongst them the famous illuminated manuscript book The Däräsge Maryam

Book of Revelation [Fig. 12].[27]

Fig. 12

in the paintings [Fig. 11].[26] Webe endowed the church

with many treasures, amongst them the famous illuminated manuscript book The Däräsge Maryam

Book of Revelation [Fig. 12].[27]

Schimper’s years of hardship

During the battle of Däräsge on 9 Feb. 1855, the rebel leader, Kasa Hailu, defeated Webe and had himself crowned Emperor Tewodros II in Däräsge Maryam church on 11th February. In order to maintain his grasp on power Tewodros was forced to continue with fighting many rebellions and uprisings throughout his realm. According to Rubenson, traditionally, most soldiers were only armed with spears and shields, but he had captured 7,000 firearms from Webe at the battle of Däräsge Maryam alone, which gave him a huge advantage over all other pretenders standing in his way.[28]

Schimper, as a former protégé of Webe, lost his governorship of Enticho. He retreated to Adwa where he lived in greatly reduced circumstances for the next few years, having lost his offices, houses, and goods. In addition, nearly all his botanical and zoological collections had been plundered[29] and he found it virtually impossible to carry out any scientific work. He was reduced to begging from those he had helped earlier on, starvation and epidemics stalked the land.

Schimper knew the members of the German Protestant artisan mission, sent from St Chrischona near Basle, Switzerland, for missionary work to Ethiopia. Their missionary endeavour first under Webe, then under Tewodros did not bear fruit. Johann Ludwig Krapf (1810 – 1881) left an account of his work and travels. In it he mentioned that on his fourth journey to Ethiopia in 1855, he had asked Ato Wolda Rufael, the custodian of the house in Adwa where other missionaries, Carl Wilhelm Isenberg (1806-1864) and Samuel Gobat (1799-1879), later Anglican Lutheran bishop of Jerusalem with oversight of Abyssinia, had lived, what had happened to the Amharic Bibles. Rufael told him, that he had sold and given them away, only 50 copies remained, in the storeroom of Schimper, ‘but he had taken the key with him’.[30]

In 1861 Christian Friedrich Bender (1827-1875), a member of the German Protestant artisan mission, married Schimper’s eldest daughter, Yäsimmäbet, in Adwa. He. Together with his fellow missionaries he lived at Gafat, near Tewodros’ capital of Däbra Tabor, where they ran a mission school and a technical training workshop. Today only two remnants of stone walls are visible.

Two years later Gottlieb Kienzlen (d. 1865), also a member of the mission, obtained Schimper’s permission to marry his second daughter, Taytu. On the orders of Tewodros, Kienzlen and all the other Europeans residents of Gafat, were forbidden to leave the area, so that the bridegroom could not travel to Adwa, but Schimper as the father of the bride had to take Taytu from Adwa to Gafat for the wedding. When he tried to return he was forbidden to leave. He was kept under ‘house arrest’ in Gafat along with all the German Protestant artisan missionaries who were forced to manufacture weapons in the form of cannons and mortars for Tewodros’ army. There were many reasons for the enforced stay in Gafat, the deteriorating political situation between Tewodros and Great Britain, triggered by the death of the British Consul Walter Plowden[31] in 1860, the ever growing mistrust of Tewodros of Europeans in his country and hence the order to allow them residence in one place only.

Despite the limitations on movements put on the Europeans in Gafat, Schimper was able to go on collection trips. He collected plants and rock samples and began working on a large map making project of the topography of Bägemder and Tigray. He was not trained as mapmaker or geologist, but wanted to study the link between the subsoil conditions and the cultivation, fauna and flora of the land. How he carried on doing this exacting scientific research work under extremely difficult situation, is hard to imagine and shows his mettle. As his first set of maps and notes had been lost through looting more than ten years earlier, he was obliged to write it all down again either from memory or from his notes, originally made in triplicate and hidden in two unnamed villages.[32]

In early October 1867 all Europeans were forced to move to Mäqdäla, Tewodros’ mountain fortress together with all his army and camp followers. Although the distance was only some 160 km to the south-east they did not arrive until March 1868 due to the immense task of hauling the cannons and weapons over the difficult mountainous terrain. Schimper commented on the harsh conditions of captivity in Gafat and on the march, as did Guillaume Lejean in his book on Abyssinia. ‘Strictly watched as the captives are, and forbidden to write, we may well wonder how it was possible for any of them thus to compile a lengthy report, containing much which, if discovered, would certainly have brought down the Emperor’s [that is Tewodros] vengeance upon them. And, indeed, the compilation of the report was no easy matter. Dr. Blanc says on this point – “I [Schimper] was obliged on two occasions to burn my report; first, on being made prisoner in April, 1866, when we thought it advisable to destroy every note, letter, or paper in our possession. At Gafat I began to write it for the second time, but after the events that occurred there, I seized the first opportunity of making away with it. At Mäqdäla it is exceedingly difficult to write; spies are constantly peeping into our tent on some pretext or other. The risk and penalty are great, as the order is, that anyone found writing is to be chained hand and foot.”’[33] This report is corroborated by Schimper’s own experience. Equally, some of Schimper’s comments on the morality of Ethiopians mirror those of Blanc’s. Some comments in the manuscript books show Schimper as a man of his time, caught up in colonial thinking on the superiority of European ways of living in comparison to what he had encountered in Ethiopia.[34]

The Europeans were finally rescued from Mäqdäla by the British military expedition under General Sir Robert Napier (1810-1890), whose troops besieged and captured the fortress on 12 April 1868 and liberated all prisoners.[35] Schimper, having sent his third collection of 1847-1848 to the Kew Herbarium in London, sent his manuscript books to the British Museum after the liberation in the hope of receiving further collecting commissions.[36]

Following his liberation by the British, Schimper returned to Adwa where he spent the last years of his life. His wife, Mersit, died on 5th February 1869 and he is known to have married again and had further children. He continued to write reports on Ethiopia, such as the one to the German Consulate in Alexandria about the coronation ceremony of the new Emperor Yohannes IV on 21st January 1872.[37] In another report he also described the maltreatment by Yohannes IV of his daughter Taytu who, after the death of her first husband Gottlieb Kienzlen in 1865, had married again. This time, her husband was the pretender-to-the-throne, Kasa Golğa,[38] in 1868, who had received the governorship of Enticho province in the same year.[39] In Schimper’s last known letter, of 8 May 1878, he described the misery of hunger in Tigray.[40]

Schimper died in Adwa on 10th October 1878 from an epidemic disease, believed to be cholera. He was 74 years old. Schimper’s son Engedasät had left Ethiopia with the British in the spring of 1868 and first studied at the St. Chrischona Pilgermission in Basle and then attended the Polytechnic School in Karlsruhe, supported by a bursary from the Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden (1826-1907). After ten years of studies in Europe Engedasät returned to Ethiopia, too late to see his father alive.

Schimper’s Observations and Maps

Schimper is known for his botanical research in Ethiopia and for his correspondence with famous botanists in Europe. In it he commented on political, economic and social conditions in his adopted country, about which not much was known to Europeans. A recent search in the British Library in London brought to light two large records, the first a large manuscript book Observations,[41] the second a collection of maps and profiles, Maps.[42] Both the manuscript book, dated 1868, and the maps and profiles, dated 1864/65, were purchased from Schimper by the British Museum, in 1870.[43]

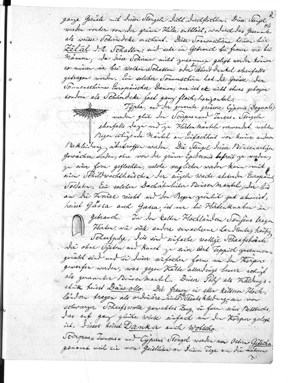

In his manuscript book Observations, written in German, Schimper introduces the reader to his detailed and extensive descriptions of Ethiopian natural history, geography, botany, food production, local medicines, and meteorology, illustrated with his own sketches.[44]

The manuscript book starts with a list of maps and profiles, followed by a preface with Schimper’s signature and 202 folios, some with little sketches, e. g. a parasol or a shade, called zelal, and a so-called ‘coat of bulrushes’, called gässa: Both are produced from rushes which grow in wet places. The stems of the Scirpus and Juncus species, called säddi and gadima, serve as sticks for the parasols, which are woven like a flat disk; it therefore cannot be closed or opened. The stems of the Typha and Cyperus species are used in a similar way for a type of raincoat. The green outer husk is removed, the long stems are gathered together at one end and interwoven horizontally by shorter stems, forming thus a cone-shaped covering which reaches down to the knees of the wearer. This coat of bulrushes is still worn by herders today [Fig. 13]. [45]

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

The manuscript book also includes comments on the character of the vegetation in Tigray, and the formation and shapes of the mountains in the district Urahut near Addigrat. There are long chapters with passages on the political situation, on Schimper’s life and income, working methods and contacts in Ethiopia as well as in Europe. The appendix is a very thorough list of plants growing in Tigray, a treatise on the understanding of Ethiopian medical science, herbal remedies against tapeworm, agriculture, cultivated plants, interspersed with narratives on the politics and personalities of Ethiopian life and finally geological observations. An example about plants: ‘Grapes are called Weini and Wein-Tetsch is the wine made from grapes; however, grapes and wine are rarities in this country although one could have both in abundance. Making wine is too much work for the careless Abyssinians, they therefore drink honey wine which is ready for consumption after three to eight days’.[46]

Schimper’s Observations or notebook is the earliest consistent presentation of the geology and botany of Tigray and throws light on soil conditions, crop conditions, population centres, language distribution and political events. A few drawings of farm implements conclude this volume.

The second manuscript, Maps, is a collection of maps, sectional drawings and topographic profiles, bound together as one volume; it comprises a large map of Bägemder[47] as well as smaller maps of the Axum – Adwa region[48] and Kolla Noari,[49] profiles of mountain ranges of Tigray, in colour, with captions and copious comments in German on the maps and in the accompanying texts, ‘Remarks complementing the tables showing the area of Adwa and Aksum in Tigray’. Here we find descriptions in great detail of the various geological strata.

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Schimper’s Maps and Observations are very important records for the area in which Däräsge Maryam is situated. Due to his prolonged stay in the area, he not only drew the mountain profiles pinpointing Däräsge Maryam, but also described an earthquake and freak weather occurrences and the treatment of a dog bite experienced there, as well as the rich flora of the whole area.[50]

Schimper’s linguistic expertise comes to the fore in an alphabetical index of place names, as used on the maps and profiles. This is of particular interest to geographers today, as many place names refer to villages and towns no longer in existence [Fig. 14]. The alphabetical index of place names is possibly of greater special interest to linguists, as he listed variants and pronunciation details. Schimper introduced it with the following observation:

Place names on the map of Bägemder.

The somewhat incorrect way of spelling place names on the maps of Abyssinia, so far published, has made me realize that it was important to write as correctly as possible the names on my map, although it only deals with a small part of the country. In order to do so I hired a local scholar, born and bred in Bägemder, who accompanied me on my trips and who wrote down the place names in Amharic wherever we went. Some of the English and German missionaries, who have a training in philology, checked his work and were kind enough to write down these names according to German pronunciation. They have been entered in an alphabetical list so that one can check the names, which might not appear written correctly on the map. One therefore has to keep in mind that the place names are written according to German pronunciation.[51]

A comment by the author of the epilogue to the article ‘Geognostische Skizze’, Richard Kiepert,[52] might have triggered this meticulous listing of place names. Kiepert pointed out that Schimper had omitted to add symbols to the place names, so that the importance of a particular place was not easily visible. Schimper only used rings to pinpoint villages and crosses to pinpoint churches, he did not use more detailed symbols, for instance for Gässa Schimper, indicating whether it was an estate or homestead.[53] In various archives in Europe there is supporting correspondence in German, explaining how Schimper worked on the large mapmaking project.

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

In addition, Schimper collected rocks, numbered from 1 to 54 and

labelled, and packed them into parcels, numbered from 1 to 15, corresponding to

the 15 drawings of Mountain Profiles in his book Maps.[54] He sent the samples to

the Natural History Museum, London [Fig. 15][55] and the Museum für

Naturkunde, Mineraliensammlung, Humboldt University, Berlin [Fig. 16]. A

Fig. 16

‘Memorandum‘, written in London, specified that ‘The figures and letters on the

parcels of rocks and the rocks themselves correspond with letters and figures

inserted on Schimper’s maps and sections. In determining, therefore, the

character of the rocks sent home these letters and figures should be preserved

for the purpose of constructing a geological map’.[56] ‘Biet Bendelion’ or

Betä Päntälewon, for instance, features on the label of a rock and, in

addition, Schimper drew the location of the church on the hill Däbrä Päntälewon

near Aksum in the Mountain profiles [Fig. 17].[57]

Fig. 16

‘Memorandum‘, written in London, specified that ‘The figures and letters on the

parcels of rocks and the rocks themselves correspond with letters and figures

inserted on Schimper’s maps and sections. In determining, therefore, the

character of the rocks sent home these letters and figures should be preserved

for the purpose of constructing a geological map’.[56] ‘Biet Bendelion’ or

Betä Päntälewon, for instance, features on the label of a rock and, in

addition, Schimper drew the location of the church on the hill Däbrä Päntälewon

near Aksum in the Mountain profiles [Fig. 17].[57]

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Finally, a word on Schimper’s style. The writings of the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel (1770-1831) on reason and the search for truth[58] gave rise to the idea of science as an exact discipline, using observation, classification and categorization; it was one of many theoretical approaches around 1800. Schimper, in his botanical writings, used a system of plant classification, which was based on the botanical taxonomy of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and one of the most fundamental ideas of the Enlightenment: the idea of classifying the world by naming, structuring, organizing and collecting its parts, which still influenced 19th-century botany. Thus, Schimper employed a ‘European’ system of classification, though he gave the plant names in the local languages, Amharic and Tigrinya, and, therefore, is a unique and complex source for today’s research on the flora of Ethiopia. In this way his writings as well as his actions can – at least partially – be described as ‘European’, in so far as he used non-local classification. Unfortunately, Schimper never gave precise locations for plants, a lack of information keenly felt by the botanical research community today.

Schimper’s understanding of nature is didactic, often referring to the usefulness of plants for cultivation and consumption both in Ethiopia and of Ethiopian plants to be cultivated in Europe or simply referring to their beauty. In this sense, he was not ‘only’ a botanist, a topographer, a meteorologist, a seismologist or a linguist, but a seeker for that which was considered to be ‘truly scientific’. Therefore, there was no inconsistency in classifying e. g. plants, stones and rivers, but also people by writing about ‘the moral character’[59] of the Ethiopians, ‘the major evil of the Turks’[60] or placing his anti-Semitic resentment.[61] By this, he fashioned himself as a ‘European scientist’ that spared no trouble in classifying, measuring and collecting. Both, ‘scientific insights’ and Eurocentric stereotypes are part of a more comprehensive rhetoric of a community of ‘European scientists’, a community which G. W. Schimper wanted to be a part of.

Captions and Photo credits

1, Portrait of G. W. Schimper. © Rheinisches Bildarchiv. Theodore’s Artisans and their Wives. WRM/PH/SL888/52. Schimper, sitting in the middle, behind him, standing, with beard, Eduard Zander.

2, Specimen sent by

Schimper. ‘Schimperi iter Abyssinicum. Pterygocarpus abyssinicus Hochst.’,

dated 19th July 1838. Kew 41177. Kew Herbarium, London; Catalogue

published on internet site:

http://apps.kew.org/herbcat/getHomePageResults.

3, Specimen sent by Schimper. ‘Oxystelma pterygocarpum Hochst.’, dated 19th August 1854, Kew 40298. Kew Herbarium, London; Catalogue published on internet site: http://apps.kew.org/herbcat/getHomePageResults.

4, Ubyaea schimperi’ = now called Haplocarpha Schimperi (Sch. Bip.) Beauv. Schimper 1176, Asteraceae (Compositae) or Ethiopian daisy, dated 30 May 1838. Kew Herbarium, London; Catalogue published on internet site: http://apps.kew.org/herbcat/getHomePageResults.

5, Ubyaea schimperi, photographed on November 14th, 2009, outside Däräsge Maryam Church, near Mekane Berhan, Semen Mountains. © Dorothea McEwan.

6, G. W. Schimper, Maps, 17, detail of ‘Area of Axum and Adwa and surroundings’. © The British Library Board. Add. Ms. 28506.

7, ditto, 17, Table 7, with entry for ‘Gässa Schimper’ and ‘Amba Sea’, Schimper’s country estate south of Amba Subhat. © The British Library Board. Add. Ms. 28506.

8, G. W. Schimper, fold-out map, ‘Umgegend von Axum und Adoa in Tigre’, accompanying the article ‘Geognostische Skizze der Umgegend von Axum und Adoa in Tigre’, as recorded by W. Schimper, edited by A. Sadebeck, with a postscript by Richard Kiepert, 1869. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, 347-352. Plate VI, profile V.

9, Exterior of Däräsge Maryam church. © Dorothea McEwan.

10, The ‘castle’ or ‘House of Refuge’ in ‘Byzantine style’, between the two concentric stone walls around the church compound of Däräsge Maryam, built by Schimper and Zander for Webe. © Dorothea McEwan.

11, Painted borders, in the church of Däräsge Maryam, possibly by Schimper and E. Zander. © Dorothea McEwan

12,The Däräsge Maryam Revelation. Robin and Dorothea McEwan (eds.), Picturing Apocalypse at Gondär, Torino, 2006, 75. Däräsge Maryam Revelation, 40v and 41r, Rev. 7:11-12. ‘And all the angels standing around the throne…’ © Dorothea McEwan.

13, G. W. Schimper, Observations, 86r. Drawings and explanations of plants used in making a parasol and a protective cloak of bulrushes. © The British Library Board. Add. Ms. 28505.

14, G. W. Schimper, Maps, 1r. Place names on the map of Bägemder. © The British Library Board. Add. Ms. 28506.

15, Rock samples, Natural History Museum, London, in Schimper’s handwriting. © Tony Betts, London.

16, Rock sample, Berlin, Museum für Naturkunde, Mineraliensammlung. ’Between Amba Berra and Biet Bendelion, South East of Aksum, c. 14 1/3 degrees Northern Latitude, Tigre, Abyssinia. Collection Schimper, plate 12, no 44’. Quartz. © Location and photo: Museum für Naturkunde, Mineraliensammlung, Berlin, Germany.

17, G. W. Schimper, Maps, 17. Table 12.

Profile between ‘Amba Berra’ and ‘Biet Bendelion’ (=Betä Päntälewon), South East of Aksum. © The British Library Board. Add. Ms. 28506.

[1] Today, his specimens are in the following collections:

Austria: Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Botanische

Abteilung, Austria.

Belgium: Natural History Museum, Brussels;

National Botanical Garden of Belgium, Meise.

Denmark: Museum Botanicum Hauniese, Copenhagen.

Ethiopia: National Herbarium, Addis Ababa.

France: Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle,

Paris; Herbier d’Université Montpellier II, Montpellier.

Germany: Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum,

Berlin-Dahlem; Botanische Staatssammlung, Munich;

The Netherlands: Nationaal Herbarium Nederland,

Leiden University. Nationaal Herbarium Nederland, Wageningen

University.

South Africa: South African

Biodiversity Institute, KwaZulu-Natal Herbarium, Durban; South African National

Biodiversity Institute, Compton Herbarium, Capetown.

Sweden: Swedish Museum of Natural

History, Department of Phanerogamic Botany, Stockholm.

Switzerland: Conservatoire et

Jardin botaniques de la ville de Genève, Geneva.

UK: Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew,

London and Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.

USA: Arnold Arboretum, Harvard

University, Boston; Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis; The William and Lynda

Steere Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden, New York; United States

National Herbarium, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

[2] For Schimper’s life see Encyclopaedia Aethiopica [from here onwards abbreviated to EA], ed. by S. Uhlig et al, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2010, vol. 4, 573-575; Annie Betts and Tony Betts, A Princess in the Family. The Story of Georg Wilhelm Schimper and his Descendants from 1804-1968, Burgess Hill: Domtom Publishing Ltd. 2010; Gerd Gräber, ‘Georg Wilhelm Schimpers abessinische Zeit (1837-1878)’, in Verein für Naturkunde, Mannheim, 6, 1999; Gerd Gräber, ‘Die befreiten Geiseln Kaiser Tewodros’ II. Aus dem Photoalbum der Royal Engineers 1867/68’, in Aethiopica, International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies Hamburg, 2, 1999, 159-182.

[3] Georg Wilhelm Schimper, ‘Wilhelm Schimpers Reise’, in Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung, Augsburg, 4.02.1843, Beilage no. 35, 273.

[4] Gerd Gräber, ‘Georg Wilhelm Schimpers Abessinische Zeit (1837-1878)’, Jahresbericht, Verein für Naturkunde, Mannheim 6, 1999, 47-68, in particular 51.

[5] Ras is a military and also a court title, usually hereditary, sometimes borne by minor princes of Solomonic blood.

[6] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 33v.

[7] G. Gräber, 1999, 54.

[8] J. B. Gillett, ‘G. Schimper’s botanical collecting localities in Ethiopia’, Kew Bulletin, vol. 27, 17 Aug. 1972, 121.

[9] Kevin O’Mahoney, The Ebullient Phoenix, A History of the Vicariate of Abyssinia. Asmara: Ethiopian Studies Centre, 1982, 36.

[10] Wäyzäro is a form of address for married women.

[11] Abba, father, is a title for religious leaders.

[12] The name for an administrator directly answerable to high representatives or royal appointees, see EA, entry ‘Šum’, vol. 4, 761-762. Albert Rodatz, ‘Auszug aus dem Tagebuch des Capitän Alb. Rodatz, Schiff ‘Alf’, betreffend einen Besuch von Massowah aus bei Dr. Schimper im Inneren von Abessinien, und Weiterreise von Massoah bis zur Umschiffung des Cap Guardafui, in Das Ausland, Ein Tagblatt für Kunde des geistigen und sittlichen Lebens der Völker, Stuttgart und Augsburg, 1846, vol. 19, 136.

[13] Enticho was actually in the hands of William Coffin, an Englishman, who had participated in a number of military campaigns in Ethiopia. The move to release Coffin from his post and to appoint Schimper may be seen as a way to limit British influence. Coffin had accompanied Henry Salt on his travels, but stayed on in Ethiopia and eventually settled in the Adwa area. Following a mission to London in 1827 he returned five years later with 1,850 muskets and carbines, which Sven Rubenson credits to be the first large-scale import of arms into the country. Sven Rubenson, 1976, p. 107. See also EA, entry ‘William Coffin’, vol. 1, 765-766. The topic of arms procurement surfaces again and again in Ethiopian history.

[14] According to de Jacobis, Schimper paid 3,000 Maria Theresa-Taler for the estate with a view to turning it into a model Catholic community. Giustino de Jacobis. Scritti. 2. Epistolario. CLV Edizioni Vincenziane. Tipografia Giammarioli-Frascati, 2003, 678.

[15] See EA, entry ‘Entičäw’, vol. 2, 318-319.

[16] G. W. Schimper, Maps, British Library, Add. Ms. 28506, 17, Table 7 with entry for ‘Amba Sea’ and for ‘Gässa Schimper’; see also G. W. Schimper, Observations, 178v, ‘Amba Sea’. On Amba Sea see also Albert Rodatz, 1846, 127-184.

[17] ‘Geognostische Skizze der Umgegend von Axum und Adoa in Tigre’, as recorded by W. Schimper, edited by A. Sadebeck, with a postscript by Richard Kiepert, 1869. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, with two fold-out maps, 347-352.

[18] A. Rodatz, 1846, 147.

[19] Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, Landesarchiv, 1831-1844. Collections: E 70t Bü 208; E 40/59 Bü 104; E 200 Bü 449; E 14 Bü.

[20] Submission to the State Chancellor, Clemens Wenzel, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg (1773-1859), in 1847, Vienna. Further similar requests by Schimper were made to William I, King of Württemberg, in 1843 and to the German naturalist Theodor von Heuglin, 1855.

[21] Annie and Tony Betts, 2010, 52. See also the letter Schimper wrote to his brother Karl Friedrich Schimper on 6.5.1848, in which he mentioned that he had appointed a manager to look after this affairs in his absence on collection expeditions, in Hans Götz, Georg Wilhelm Schimper, der Abessinier. Auszüge aus dem Schimperschen Nachlaß, Schwetzingen: Schriften des Stadtarchivs no. 14, 1990, 67.

[22] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 5v, ‘… eine Art kleines Schloss‘.

[23] G. W. Schimper, ‘Meine Gefangenschaft in Abessinien’, in Petermann’s geogr. Mittheilungen, Heft VIII, 1868, 294-298, quote 296. Theodor von Heuglin, Reisen in Nord-Ost-Afrika. Tagebuch einer Reise von Chartum nach Abyssinien, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Zoologie und Geographie unternommen in dem Jahre 1852-1853, 1857; he used the word ’building’, in German ’Gebäude’, 69.

[24] The asylum charter is extant in two versions, one kept in London, BL, Or 481, 3v and the other in Paris, BNF, Eth. 112, 2r. Manfred Kropp, ‘Asylrecht und Pfründe für die zukünftige Residenz: Die Zeugenfassung der Privilegurkunde des Ras Webé für die Marienkirche von Däräsge aus dem Condaghe der Hs. BL Or 481, 3v’, in Studia Semitica. Journal of Semitic Studies, Jubilee Volume. Manchester, 2005, 193-206. See also Dorothea McEwan, The Book of Däräsge Maryam, Wien: LIT Verlag, 2013, in particular 62-67. G. W. Schimper, Observations, 4v, ‘…ein politisches Heilightum…’

[25] Richard F. von Neimans and Wilhelm Schimper, ‘Über die politischen Zustände Abessiniens, in Ausland, 31, Stuttgart und Augsburg: Verlag der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1858, 877-880; ‘Krönungshaus‘, 877.

[26] Friederike von Krosigk, Ein Weizenkorn fliegt gegen den Wind. Abenteuer eines Deutschen in Äthiopien. Mühlhausen: Bergwald, 1938, 111; Clements Markham, A History of the Abyssinian Expedition, London: Macmillan and Co., 1869, 64.

[27] Robin and Dorothea McEwan (eds.), Picturing Apocalypse at Gondär, Torino: Nino Aragno Editore, 2006.

[28] Sven Rubenson, King of Kings: Tewodros of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University; Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1966, 74.

[29] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 5v.

[30] Johann Ludwig Krapf, Reisen in Ost-Afrika ausgeführt in den Jahren 1837-1855, 2 vols, Kornthal, 1858, vol. 2, 335-336.

[31] Walter Chichele Plowden (1820-1860), British Consul at Massawa from 1848 to his death. Plowden was murdered during his journey from Gondär to Massawa by Leğ (prince) Garäd Kenfu, a follower of Agäw Negusé, the nephew and political heir of Webe. He is buried in Gondär. See EA, vol. 3, entry ‘Negusé Wäldä Mikael’, 1166-1167.

[32] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 5v-6r.

[33] Guillaume Lejean (1824-1871), Theodore II. Le nouvel empire d’Abyssinie. Paris; Amyot Editeur, n.d., edited in English by Sir H. Blanc, The Story of the Captives. A narrative of the events of Mr. Rassam’s Mission to Abyssinia etc. London, 1868, v. Sir Henry Jules Blanc (1831-1911), a medical doctor from the Bombay Medical Department, was a member of the Abyssinian mission of the British Agent Hormuzd Rassam 1864-1868; Blanc became the First Assistant Secretary to Colonel Merewether (1825-1880), British Resident at Aden, later Major General Sir William Lockyer Merewether.

[34] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 114v.

[35] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 6r-6v.

[36] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 7r.

[37] Anonymous, ‘Neues aus Abyssinien’, Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde. Berlin: D. Reimer, 7, 1872, 270-272.

[38] EA, entry ‘Kasa Golğa’, vol. 3, 349-350.

[39] Gustav Brüning, ‘Nachrichten Dr. Schimper’s über die gegenwärtigen Zustände Abyssiniens’, Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde, Berlin: D. Reimer, 7, 1872, 364-366.

[40] G. W. Schimper to Adalbert Geheeb, 8.5.1878. Geheeb (1842-1909) was a German botanist, specializing in mosses. In Hans Götz, Georg Wilhelm Schimper, der Abessinier. Auszüge aus dem Schimperschen Nachlaß, Schwetzingen: Schriften des Stadtarchivs no. 14, 1990, 76-78.

[41] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 1868. London, British Library, Add Ms 28505.

Writing in faded black ink, with a few pen drawings. The outside cover, in reddish-brown leather, European style, corners and spine in dark red leather and gold press marks, measures 25.5 cm x 32 cm.

Folios 1r-2v: Blue paper on cream guards, 19.6 cm x 31 cm. English ‘List of Dr. Schimper’s MSS & Maps from Abyssinia’.

Folios 3r-166v: cream coloured paper, 24 cm x 31 cm. Width of guards: 4 cm.

Folios 167r-202v: blue paper on cream guards, between 21.2 cm and 21.6 cm x 27 cm. Width of guards: 2.7 cm.

1 foldout, in colour, between f. 74 und 76.

Contents: 3r: In Abyssinia. Wilhelm Schimper’s Examination of the Vegetation.

3v: Blank page.

4r-7r: Foreword. Personal-political News.

7v: Blank page.

8r-83v: Character of the vegetation in Tigre as represented by the vegetation in the region shown on the map and by that in the Urahut Highlands in Agame province on terrain 4,000 to 11,000 above sea level.

83v: Postscript. Further comments on the vegetation.

84r-113v: Appendices to the index of plants which grow in Tigre.

Explanation of some of the local names and the way they are used. Standing of Abyssinian Medical Practice (medical conditions and methods of treatment). Herbal remedies for getting rid of tapeworm, which is generally widespread In Abyssinia. How the tapeworm comes into being, its development, its effect on the human organism and the reason for it being so widespread. Arable Farming and how the weather affects it. Cultivated plants, their use (bakery, general cooking, beer brewing) and their commercial exploitation.

Some anecdotes occasioned incidentally where the above plants have been the subject of 114r -138v: Arable farming In Abyssinia. Enumeration of the most commonly cultivated useful plants.

152v -166r: Medical problems in Abyssinia and some observations on medical knowledge and practice of the Abyssinians.

167r -202v: Geological Observations in Abyssinia, continued in BL, Add Ms 28506, 5r – 12v.

[42] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 1864-65, London, British Library, Add Ms 28506.

Writing in faded black and red ink, maps in grey, blue, red, yellow paint.

The outside cover, in brown leather, gold press marks on spine, measures 50 cm x 74.5 cm.

Inside, the cream coloured paper measures from middle fold to edge 48 cm x 73 cm.

Contents: Folios 1r to 2v: cream coloured ruled paper: Place names of the map of Bägemder, 40 cm x 26 cm.

Folios 3 and 4: cream coloured ruled paper: Place names of the map of Aksum and Adwa, 38 x 47.5 cm.

Folios 5r to 12v: blue ruled paper: Notes on the sectional drawings of the map of Aksum and Adwa, 23 cm x 2.7 cm. Tables 1 to 15, with Tables 4 and 13 not listed.

Fol. 13r: Memorandum, in English, cream coloured paper, 26 cm x 20 cm.

Fol. 14: Map of Bägemder and The shore of Lake Tana. Papers stuck together, overall size 132 cm x 130 cm. Dated 1864/65.

Fol. 15: Tabula A, B, C. A), Survey of the Main Mountain Types and their usual grouping in and around Bägemder. B) Analysis of the Downward Slopes in Tigre.

C) The Progression of Grey Granite into Red Granite between Tigre and Tsalamt.

Fol. 16: Map of Kolla Noari [or Qwälla]. The dimensions of the map are 45 x 35.5 cm.

Fol. 17: Map and sectional drawings of the mountain ranges near Aksum and Adwa.

Fol. 18: Sketch of Aksum and sectional drawings of the mountain ranges near Aksum and Adwa. The dimensions of the maps are 50 cm x 34 cm

Fol. 19: 7 Tables, sectional drawings of the Bägemder map.

[43] I am indebted to Annie and Tony Betts for drawing my attention to the following letter, dated 19th July 1870 from John Winter Jones (1805 – 1881, Principal Librarian of the British Museum 1866 – 1878) to Edward Augustus Bond (1815-1898, Keeper of Manuscripts 1867-1878), kept in the British Museum, ‘Papers relating to the Purchase and Acquisition of Manuscripts 1866 – 1870’.

‘Dear Bond,

Herewith I send you some Manuscripts and some Geological Maps in Manuscript which, having been purchased by the Government of Dr Schimper in Abyssinia, have been forwarded under Treasury orders by the authorities at the War Office for preservation in the British Museum. They have since they first reached the Museum been sent at the request of Dr. Schimper to Professor Braun of Berlin for revision.

By direction of the Trustees I now send them to you to be deposited in the department of Manuscripts. Should it upon examination appear that the Maps are merely intended as illustrations of the Manuscripts you will of course keep all the documents together. Should you, however, find that the maps are more suitable for the departments of Maps, will you be so good as to hand them over to Mr. Major and let me know that you have done so.

Believe me, yours truly, J Winter Jones.’

[44] See G. W. Schimper, Observations, geological sketch, 28505, 198v; see G. W. Schimper, Observations, the sketch with household utensils, 88v.

[45] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 85v-86r.

[46] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 60v and 61r.

[47] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 14.

[48] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 17.

[49] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 16.

[50] G. W. Schimper, Maps, Mountain profile Tabula C, 15.

G. W. Schimper, Observations, 186r-188v, earthquake in Däräsgé Maryam on 23 February 1854; Observations, 95v, on the treatment of a dog bite and in greater detail in the ‘Aide Mémoire’, not dated, summer of 1852, in Paris, Jardin des Plantes, Botanical Library of the Museum.

[51] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 1r-4v.

[52] Richard Kiepert, German cartographer, 1846-1915.

[53] ‘Geognostische Skizze’, 1869, see footnote 12. Kiepert’s comment on p. 352.

[54] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 17.

[55] A second set of the drawings of the 15 Mountain Profiles was deposited with the numbered rocks in the Natural History Museum, London. © London, Natural History Museum, Special Col. Ms (63) Sch 1 Manuscript Shelves.

[56] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 13r.

[57] G. W. Schimper, Maps, 17, Table 12.

[58] G. W. F. Hegel, System der Wissenschaft, Bamberg/Würzburg, 1807, 139-140.

[59] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 202v.

[60] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 106r.

[61] G. W. Schimper, Observations, 98v.